No, I haven’t gone and decided to embrace some of the shadier parts of rural Michigan. I’m doing something even crazier. I’m building furniture.

If you’ve followed this site at all, you’ve seen the recent videos for Chris Schwarz’ new book The Anarchist’s Tool Chest. I received my copy yesterday and finished it up tonight; here are my impressions after the first read.

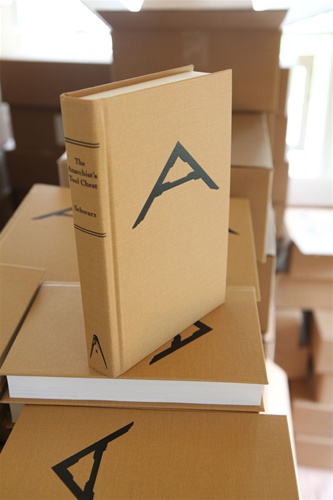

First off, the book itself is a beautiful object. It has a lovely solid cover with an embossed graphic, no silly paper dust jacket to get torn up and lost. The cover has a texture to it, so it won’t slip when placed on a stand or your lap. It’s a good size, and has the feel and look of an old book. The paper is heavy and crisp, the type is wonderfully set, with some nice little touches in the typography. There’s no colophon, so I’m not sure what fonts were used, but the type is easy on the eyes and well spaced.

The book is a story in three parts: why you should build things yourself, what tools you’ll need to do it, and finally, where to store those tools so they will outlast you. Unlike many of the books published under the Popular Woodworking label, which tend towards a collection of articles, this has a narrative and a coherence that makes it an enjoyable read, more like a novel.

The first part, why you should build for yourself, struck a chord. I strongly dislike most manufactured furniture, especially Ikea’s furniture. My father taught that it’s better to buy a quality thing once, rather than buy a cheap thing ten times, and I’ve ended up kicking myself every time I’ve forgotten this maxim.

To that end, as my wife and I have been furnishing our home, we keep moving up the retail ladder. First, I picked up a bedroom set from Ethan Allen. Looks nice, but after living with it for a while, the build quality is only OK. The Stickley living and dining room stuff we purchased later (after saving many pennies) is better, but even that has some quality niggles. And going back to the showroom now, I don’t see Stickley getting better. Boards in top glueups are getting narrower. Joints look sloppy.

In the second part of the book, what tools you’ll need to build quality furniture, Chris doesn’t pull any punches. His thesis is that you only need about fifty different tools to make just about any common piece of household furniture. Yes, only fifty tools, and none of the fifty are power tools. He advises that you should buy the best you can afford, trying to buy such that you’ll never have to buy again.

As the (soon to be former) editor of one of the more popular woodworking magazines, I think it takes some testicular fortitude to say straight out that it would be better for most folks to limit their tool set and buy tools that you only have to buy once. He does include some power tools in the margins, things that will make life easier, but not the standard table saw. The shop as described is much more centered around the workbench, not the power equipment. The powered gear exists like a shop apprentice of old, dealing with the drudgery of milling rough lumber.

The third part, how to build a chest that will hold your tools so they’ll last a few lifetimes, is more like the workbench books; here’s what we’re going to build and here are the rules for how to design and construct it. The writing and pictures are clear and concise and have me seriously considering building a tool chest instead of the hanging tool cabinet for the Hand Tool School final (sorry Shannon). [ed note: definitely building a tool chest instead of a hanger after I proved gravity works]

Throughout the book, Chris punctuates his point with personal stories from the journey down the path. It’s a much more personal book than anything he’s written before and I enjoy that touch. The writing is top-notch.

Give the book a read.

19 replies on “A Review of The Anarchist’s Tool Chest”

Ha ha Ben, I admit to considering the same thing. I will probably end up building a chest some day anyway. Of course this will be because of a strict violation of the principles Schwarz lays out in Chapter 1: I have a lot of tools. I have always been drawn to the chest form for tool storage from my first visit to Williamsburg and then it was strengthened when I became a volunteer in a 19th century joinery that has 3 of these chests. The problem is I do not have the floor space for a chest like this. Whether I eventually overhaul my shop or move to a different space, one of these will eventually end up in my shop. Great review, I should finish up the book tonight myself.

The afterword is my favorite part of the book.

The book is set in Cochin, Cochin Italic, and Frutiger. And labelmaker.

The labelmaker was a touch of genius.

You keep it up now, udnesratnd? Really good to know.

[…] If you would like to read the full review, click here. […]

Really nice review. I finished the second read last night. This will have a permanent home on my bench as I continue to grow my skills and tools.

-T

Loved this book, too… but I have a complaint. Nowhere is the cost of this humble toolkit really addressed. Schwarz will often use terms like “affordable” and “for a song” but he also has the connections and tool-buying experience to find these deals. For a novice, it is daunting and easy to waste time and money buying inferior tools. At the same time, he suggests that when tools must be new, they need to come from a top maker. He tends to use LN as his major supplier, so it is easy to look up the costs of these tools.

His “minimalist” kit would cost many thousands of dollars. Arguably cheaper than a full powertool shop, but here is the thing: when you drop $300 on your box store table saw, you can do quite a bit with it on day one. Nothing as artisinal as a dovetailed toolchest, but you can make shop furniture, simple outdoor chairs and tables, birdhouses, etc on day one with nothing more than a screwgun.

To do even the simplest projects such as the packing box in “the Jointer and Cabinetmaker”, however, you need to have your grandfathers tool collection, spend about $2000 for a minimal kit (nowhere near the full 50), or you can spend years accumulating and rehabilitating antiques. You’ll need a friable wheel for your grinder, a set of sharpening stones, and the skills to use them, of course.

My complaint is not with the nature of economics or the fact that woodworking is an extremely expensive craft; it is that this fact is constantly swept under the rug. The Anarchist’s Tool Chest seems to inspire confidence by telling you all you need to know about buying used tools, but his sample prices for how cheap some cools can be are not honest. Perhaps this varies regionally – perhaps in his area of Kentucky old tools are overflowing from every attic. Out here in the west, though, they are either sternly hoarded, rusted, or both. It is nigh-impossible to folding rules, hand drills, and the like for prices less than ridiculous.

I feel the book needed a brief section, “So you wanna try a dovetail cut? That will cost you $3500, workbench not included” and then mention some coping strategies for the average person.

Its also a little ironic that Schwarz preaches this tool minimalism, while simultaneously bragging about his $2000 plane plow and so on. He mentions a “half set” of rounds for someone wanting to save vs the full set, not mentioning that even a quarter set is the cost of a reasonable used car.

Again I am not opposed to these costs and whining about them will not change reality. I do feel, though, that the book is lacking in not addressing this. How can a typical person dip their toes in the world of woodworking when you really cannot go very far without the whole set. So you get ahold of a jack plane and a dovetail saw… now what? The jack plane might let you get a reasonably dimensioned board, but if you want to make a little box to keep recipe cards in, you’re going to need a lot more than that dovetail saw. True, while that first card box will cost you about $4000, additional ones for the rest of your life are “free” other than the lumber, but this book really needs to be honest about that initial startup cost.

I did greatly enjoy this book – and I am selling some of my prized but unused possessions in order to make this my way of life. I agree fully with his philosophies on buying used or heirloom quality, but I do think he is taking for granted that his readers are all wealthy retirees or also editors at woodworking magazines where there is a full shop available and testing samples being thrown at them daily.

Hey rob,

Are you referring to the price of my toolkit, or the price of a generic toolkit as described in the book? My kit is a little odd, as a fair portion of it came as gifts. I could go through a total everything up though and come to a total.

For the generic kit, the price would vary wildly. Just to take one example, you can get a Jack plane a variety of ways. You could get one for $15 at a flea market and rehab it, or you could get a nice user off of hyperkitten for $35, or you could go upscale and get a Lie Nielsen for $325. For a jack plane, I think it’s crazy to go spendy, as it’s a fairly rough tool, assuming you’re using it as a fore plane.

The rest of the kit breaks down that way too. There’s a huge variability in what you can spend, and still have a serviceable kit.

Ah, sorry, the wordpress upgrade screwed me, I didn’t see your full comment until just now. Let me digest the full comment for a bit before I respond.

I agree completely with your opinion on the subject of tool buying. For a typical home hobbyist/weekend woodworker it is completely impractical to go the flea market/tool refurbishing root in a broad sense. Of course you may find tool bargains here and there but you will never completely fill a tool kit or even half of a kit going the used tool route. For a pro like Schwarz it’s much easier because he makes his living doing it, and has made many connections in the used tool world, not to mention that he can most likely write off tool purchases on his tax form.

Like you, I have no illusions on the cost of woodworking as a hobby, but I do take offense to somebody telling me that it isn’t actually that expensive.

re-reading, I hope that my criticism comes through as it was meant – a mild musing, not a real criticism. I would like to repeat that I love this book and believe fully in its concept of investing only in quality tools is very valid – I just believe that Mr Schwarz speaks from a lofty position and he possibly forgets that sometimes. The book is so close to perfection that little bits like this jump out at me like the pea in the princess’s mattress. I am deeply appreciative that the woodworking lore has Mr Schwarz’s additions, and it is indeed the kind of thing I have been waiting for. Combined with Jointer and CabinetMaker and Wearing’s “Essential”, we have a very enjoyable and very informative little library thanks to Schwarz and Joel Moskowitz.

I hear where you’re coming from. I too found some of the prices quoted a tad low, until I stumbled onto hyperkitten. With the recent resurgence in interest in hand tools, I think the market has adjusted prices to meet demand.

As for minimalism, minimal doesn’t mean inexpensive, in fact often the opposite is true. Minimal things have to be very well thought out, and for a tool kit, that means a number of the tools have to be multitaskers, and the easiest way to make a multitasking tool is to require some skill to wield it. I think saws are a prime example. They can perform a whole range of things, especially compound cuts, that would be hard to jig up on a table saw, but to get to the place where you can it, you need a good saw and time to practice.

The other thing I’ll say is that the amount of practice required to becomes proficient in wielding these tools is nowhere near as high as I thought. I’ve only been doing this for about six months, mostly evenings, mostly in two to three hour blocks a few times a week when the kids are asleep. I can cut to line and saw plumb without too much trouble now. I was terrible for about a week, but practice, and help from Shannon at the Hand Tool School and tapeing myself did wonders. Now I use a mirror to keep myself honest and track body position while sawing. Works great.

Last, the cost thing is all relative, but it’s certainly expensive to get started. The biggest barrier for me was the bench, though now I have built two, one with just a table saw and a screw gun, and the second almost entirely with hand tools, mostly a jack, jointer, chisels, saws and brace and bits. The nice thing is you don’t really need everything up front.

[…] This review from Ben at http://www.blowery.org includes a good discussion in the comments about how minimalism is not necessarily cheaper. […]

I think this book explains perfectly why self published books are known as Vanity Press. Undoubtedly Mr. Schwarz has spent a great deal of time messing about with tools and knows a good deal, but this book is largely a blathering run-on by an author without an editor. What nuggets of wisdom may be found are lost in the landslide of nonsense, hyperbole, colloquialisms, smart alec quips and stylistic affectations. The only really useful info is Schwarz’s bibliographic references

Wow, that’s quite the parroting of Gary Roberts. Have anything original to add to your remarks, or are you content to let Gary think for you?

[…] good reviews are here, here, here, and here. The comments on these reviews are often just as telling as the reviews […]

Advice is what we ask for when we already know the answer but wish we didn’t.

I’ve read the Anarchist’s Toolchest twice and while I enjoyed the book I cannot say it is a definitive entry in the subject of woodworking. The book is at it’s heart a look into Schwarz’s personal beliefs on which woodworking tools to use and how to store them. Personally I am a hybrid style woodworker who uses both hand and power tools. Many woodworkers probably fall in to that category as well. Quite a few of the tools that Schwarz suggests are unnecessary in a modern shop. As satisfying as planing a rough board down to finished dimensions by hand may be, it’s really not practical for a hobbyist woodworker who only gets a few hours a week in the shop. That’s why surface planers were made, to eliminate that drudgery. Schwarz’s plea to hobbyists: make your furniture rather than buy garbage, is part wishful thinking, part good advice. Yet if we follow all of Schwarz’s methods it would be difficult to make one piece of furntiure a year yet alone furnish a house. As I said before, making furniture strictly by hand is not very practical for most home hobbyists, unless you are lucky enough to have unlimited shop time, are retired, or both. And maybe those lucky few are the group of readers Schwarz is aiming at.

As far as the toolchest itself is concerned, Schwarz does make a nice one. But a toolchest is hardly the most necessary piece of furniture in a shop. They look nice, and do the job, and they certainly are traditional, but they are also a matter of personal taste, nothing more. In fact, if you are into making tool storage, a wall cabinet is much more practical for the home hobbyist because it doesn’t use up valuable floor space, of which most home shops already have too little. Still, the chest is well constructed and looks nice but I do have to laugh at some of the little construction details. Schwarz mentions nailing the chest bottom without glue because it may rot due to water damage and such. That was probably good advice 200 years ago in a shop with a dirt floor and no climate control of any kind, but if I have 4 inches of water in my garage I have a lot bigger problems than my toolchest’s rotting bottom boards.

The end of the book deals with Schwarz’s thoughts on the state of modern woodworking and the decline of the tradtional professional bench woodworker. While the profession itself may be in decline, I don’t think that woodworking is in any danger. From my point of view it is actually thriving. There are more quality tool manufacturers now than we’ve had probably since pre World War 2. The options for classes and such have increased greatly, as well as the number of books and magazines published. There is even more woodworking TV on than I’m used to seeing, whether you enjoy the shows or not. So I don’t think the hobbyist woodworker has anything to worry about for a long time. And maybe Chris Schwarz has something to do with that. But I can’t answer that question for sure.

As far as anarchy in the woodworking sense, I get Schwarz’s analogy but it doesn’t necessarily completely work. But I think that he uses it with a grain of salt. Most woodworkers are “anarchists” if you use his definition regardless, otherwise we would be buying furniture instead of trying to make it. But Schwarz does make several good comments of the state of rampant consumerism and the throw-away culture it creates.

All in all the book is good, but not a classic. Schwarz’s fans will like it, and maybe others who are die hard hand tool enthusiasts. Others will probably be on the fence, like myself. But I can see how some, maybe many could hate it, it can be polarizing.

If you are a hybrid worker who enjoys both methods I would suggest Popular Woodworking’s Handtool Essentials, which is a collection of articles about using handtools along with powertools in the shop. It works quite well.